High Five

January 28, 2015

A few weeks ago, my company began an experiment with HR and robots. It’s pretty interesting (or at least we think so), but before I tell you about it, there’s some exposition that needs to happen. I’ll do my best to make it worth it.

Robots

I work for Gridium, and we’re a distributed company. There is no central office, and even our founders live in different cities. We do gather everybody together four times a year, but apart from that there isn’t much face-to-face. So we spend most of our time in Slack, and we are students in the art of ChatOps.

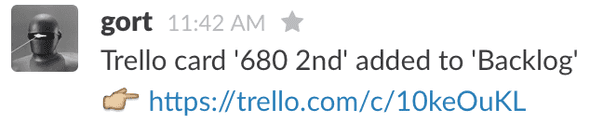

Mostly what that means is that we have a Hubot (named Gort) whose most commonly-used function is to paste links to kitten photos into our chat rooms. But we’ve also taught him to connect with Trello, so he tells us when something interesting happens:

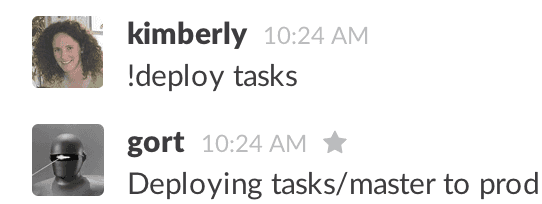

…and to Semaphore, so we can do CI and deployment:

…and to a goodly number of other services, too. We’ve turned our chat room from a water-cooler and announcement channel into the central control room. And not just us engineers, either; the Trello example above was the sales team using Slack to track the provisioning of a new customer.

ChatOps

All of that is ChatOps. That term is a little fuzzy, but it boils down to automation of repetitive technical and social activity. You can probably tell by how abstract that sentence is that I’ve thought about this a lot, but stay with me.

In the chat room, before Gort came along, you’d periodically see patterns like this when deployments were happening:

A: I'm doing a deployment, hang on to your butts.

B: Okay

C: Got it.

...(5 minutes pass)...

A: Okay, I'm done. Is the website broken?

C: Nope, looks okay to me.

B: Looks fine.

A: Great. Carry on, everybody.There’s an implied contract here. As the one doing the deployment, you’ve agreed to tell your teammates what you’re doing and when it’s done, wrap it up in a timely manner, and not to do something that gets in their way or destroys sensitive data. The rest of the team has implicitly agreed not to interfere with a deployment they know is happening, and to help out if something goes wrong. This arrangement has been pretty effective for most of the history of Internet services.

But ChatOps shows us that this can be improved, and not just a little. Most immediately, we’ve made it easier to deploy from the chat room than to do it manually. But more importantly, you’ll never forget to tell the team when you’re deploying. Or when you’re done. Or if something goes wrong. And if something does go wrong, you don’t have to stop fixing it to let the rest of your team know.

An Experiment

Automating a thing has side effects. Firstly, the fact that you’ve automated it at all says that it was worth some effort to streamline and error-proof it. Almost as importantly, you’re sending a signal that this should be effortless, that this isn’t a thing that’s made more valuable with extra sweat. That last one is important to keep in mind when you’re automating a human process, rather than a technical one.

Facebook’s birthday reminders are a perfect example of how this can backfire. Getting a handmade card in the actual mail is really touching and personal – a real human being cared enough to think about what you like, make a token of their esteem, and spend real money to send it to you. In contrast, an “HBD” posted to your Facebook profile is nearly meaningless; you pretty much only think about them in aggregate.

So automating social things is tricky, but we didn’t think it was impossible. Is there something on the softer side of the business that Gort could effectively improve? What’s something we want to do more, but don’t want to spend a ton of thought and time doing, and that wouldn’t be reduced to meaninglessness by the fact of being automated?

What about a high-five?

High Five

So we wrote a Hubot plugin that automates high-fiving:

If you’ve never used things like Slack or Hubot before, here’s what’s happening:

- We’ve configured Gort to interpret things that start with ”

!” as a command, so David can trigger a high-five pretty easily. - Gort pastes in the URL of a GIF, which Slack loads and plays for everyone. This draws your attention visually.

- Gort includes

@channelin the text of the post, which sends a notification to everyone in the room. Their computers and phones make a noise, drawing everyone’s attention audibly right now, and with a trailing notification if they missed it. - A $25 Amazon gift card is sent to Kimberly at the company’s expense.

The first three things in that list are similar to a real-life high-five. That last one, though – that would be pretty tricky to pull off without the magic of technology. With this, anyone can send anyone a “thanks!” with a monetary gift attached, in a very public way, and with zero friction.

Peer Recognition

If you have experience with HR practices, you’ll recognize this as a peer-recognition program. It hooks into the deeply-wired human preference towards recognition; people want other people to think they’re awesome, even more than they want money. “But” I hear you saying, “this involves money, too!” Oddly, the recipients of a high-five won’t actually see it that way – the gift card is more of a signal that this is serious recognition, rather than just a pat on the back. Of course, the receiver will like the money, but when they spend it on something, that thing will then remind them of the original high-five, which leads us back to the peer-recognition drive. See? That money isn’t really money.

Now this is obviously subject to some limits. You can’t high-five yourself, for instance, and there’s a daily cap on how much money a single person can give away, but we haven’t actually run into any of these yet. Part of this is the group of people I work with, who are among the least selfish and most generous people I’ve ever worked with. But some of it is that the gifts are public; you don’t toast someone at a dinner party without a good reason (or at least a good speech), and this is no different.

What Happened Next

We introduced this at an all-hands retreat in California, and the immediate uptake was pretty good: there were more than a dozen high-fives the first day alone, and a similar number in the following week. Once the novelty wore off, the general usage has been fairly steady, but it’s hard to draw any kind of conclusions from a month of usage by 13 core staffers.

We’re already seeing some interesting emergent behavior, though. One idea was to use this to send performance awards to contract employees, which turns this program into a top-down recognition program, more like a bonus. We’ve also seen some “creative” conversational uses, like trying to high-five an entire website.

What Happens Now

So this has already yielded some interesting results, and we’re only in our first month with it. We’re looking forward to seeing how it plays out over a longer period of time, and whether other teams think it’s useful enough to steal.

We’ve released the hubot-tangocard-highfive plugin into the wild, and it’s completely open-source.

Basically it just ties together a few APIs behind a pretty simplistic UI: Slack, Tango Card for the gift cards, and a Google spreadsheet for logging transactions.

This whole thing was rendered pretty easy by the thriving ecosystem around Node and Hubot, so it’s only fitting that we make this available for anyone to use.

If you end up using it at your company (or need help getting started), I’d love to hear from you.

Ben Straub lives and works in Portland building useful things. You should follow him on Twitter.